Is God willing to prevent evil, but not able?

Then he is not omnipotent.

Is he able, but not willing?

Then he is malevolent.

Is he both able and willing?

Then whence cometh evil?

Is he neither able nor willing?

Then why call him God?

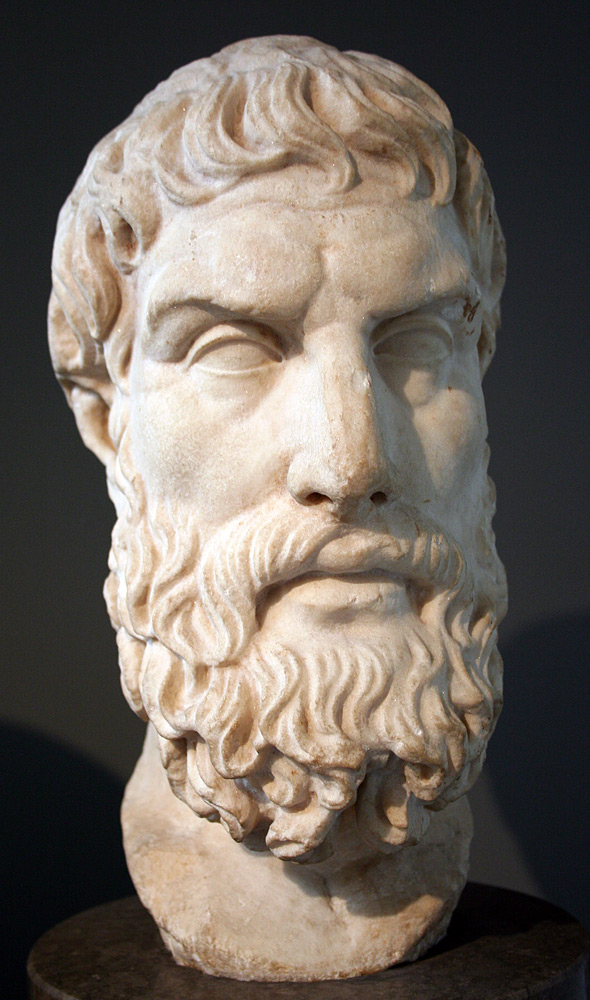

-Epicurus

When a old university friend of mine first encountered this famous, or infamous if you take your religion seriously, riddle from the Greek philosopher Epicurus on my Facebook page, she was, to put it midly, rather put out.

"This has to be one of the most narrow-minded quotes I've ever read," she said, and went on to explain that the god she believes in gave humans free choice and have the choice of doing what god wants or not. So if we use our free will for evil means, she argued, well there is not point in blaming god is there?

Of course, as passionately as she believes, my friend missed Epicurus's point entirely. He wasn't blaming god for evil. He was pointing out the inescapable paradox of the notion a god that the omniscient, omnipresent creator and ruler of everything in the universe who is also perfectly good. More simply put its the question evil, and Epicurus's little riddle hasn't been, in so far as I know, adequately answered by theists since he first suggested it. Far from blaming a god for evil, Epicurus was pointing out the absurdity of the notion of god (or gods). The very existence of evil makes an "all loving god" a logical contradiction.

This does strike right at the heart of Christianity morality as found in the Bible. "God is love" is a constant refrain among believers who regard the almighty as a benevolent source of all things that are good. Anything that isn't good simply isn't god's doing. Yet the texts themselves reveal a creature for whom the word "good" doesn't really apply even in the most liberal application of the term. True, in the New Testament god, through the figure of Jesus, only threatens humanity with eternal torture for the crime of not believing. But in the Old Testament, god is a bloody figure. He spends a great of his time murdering on a unspeakable scope. He commits global genocide at least once, order the wiping out of entire cities (save for the virgin women which his chosen people get the keep as slaves.) It is these acts of barbarism that would have made even the vicious Zeus flinch, that led Richard Dawkins to write in the God Delusion:

The God of the Old Testament is arguably the most unpleasant character in all fiction: jealous and proud of it; a petty, unjust, unforgiving control-freak; a vindictive, bloodthirsty ethnic cleanser; a misogynistic, homophobic, racist, infanticidal, genocidal, filicidal, pestilential, megalomaniacal, sadomasochistic, capriciously malevolent bully.

Now, remember, Christians believe the god who asked Job to murder his son, who personally executed the first born sons of Eygpt, who drowned all life on earth, is the very same "god of love" of the New Testament. Frankly, once you read the Old Testament, and see its blood soaked theology, the claims of the New aren't important. I don't need to know anymore about the character of this god beyond the flippant disregard for human life in stories like Noah's Arc or Exodus.

Still, to play devil's advocate, if you'll forgive the phrase, lets concede for the moment that the Christian god isn't a blood thirsty manic with a desperate need to be worshiped. Lets assume he wouldn't murder anyone. Even then, Epicurus' riddle remains true. Because if god is all powerful and all loving, then he aught to prevent evil. But, if he exists, he doesn't. He allows it to flurish whenever and where it can.

This is a particular problem. For any decent person with even the slightest concern for their fellow bi-pedal mammals knows that a failure to prevent evil or suffering when it is in your means to do so, is an act of evil. If you walked past a person on the street bleeding to death which is the ethical choice? To stop and help or just to walk past? To walk past, to make that omission of action, is in of it itself an act of evil. This is also the god of Christian theology - the loving god with the power to stop evil, but refuses to do so. That is the kind of god that Epicurus called, correctly, malevolent.

Of course, there are comment arguments from theists, most of which revolved the free will argument my friend above offered. But how does free will result in a person being killed by a random lighting strike? Or an earthquake? Or a forest fire? We are at the mercy of natural forces that can, in an eye blink, wipe us out. If one believes the Christian notion of an all powerful ruler of the universe, then god can easily prevent the deaths of innocent people from such things. Yet he does not. This is no different than steeping over a bleeding person on the sidewalk. The lack of action is an act of evil.

Which brings us back to D'Souza's claim that morality cannot exist without god. Yet if you take the texts at their word, god frequently engages in behavior that is anything but moral. The old canard that says "God's morality is not man's", or as I like to put it, "thou shalt not kill unless god commands it," is simply an excuse and is, sententially or not, a justification for every horrible act one person can inflict upon another. The foundation of this morality, the morality that D'Souza would have us believe is the only thing keeping people from riping each other apart, is scrawled in human blood.

Yet in Epicurus we find not just a skeptic about the existence of supernatural dictators. He also offered up a morality and ethic grounded in human happiness - all without the directions of a cosmic king, thank you very much. Epicurus taught that the pursuit of happiness was the highest ethic ideal. Often misunderstood by the theist set as advocating rampant pleasure seeking, Epicurus was suggesting the absence of pain and suffering - a state of being he called ataraxia : a state free from worry and fear. (In fact, he explicitly warned against overindulgence precisely because it would cause suffering) So understand that we we seek pleasure for ourselves, and for others. This is a Greek permutation of what we now call "the golden rule." You do not inflict suffering on others because you do not wish it for yourself.

Epicurus, the great critic of very notion of god or gods (if they did exist, he thought, then they are utterly unconcerned with human affairs) also admitted slaves and women into his school of philosophy - rarity in that time and place - and advocated for a human egalitarianism.

The point behind all this is that D'Souza is correct when he says some Christians behave morality because they believe. But to say that morality is impossible without a god, and in particular without the god he believes in, is ridiculous.

In men such as Plato and even more so with others like Epicurus, we see a clear ethical and moral code that teaches doing good for its own sake, for helping those who need it, and avoiding inflicting harm on others. All done without a reference to cosmic god who is always watching, judging and ready to punish. Rather it is human beings struggling with the contradictions of our nature, and find a way to live what the Greeks would have called "the good life."

Long time men lay oppressed with slavish fear.

Religious tyranny did domineer.

At length the mighty one of Greece.

Began to assert the liberty of man.

-Lucretius, an ode to Epicurus

No comments:

Post a Comment